Initiation

It was June 2001, Richmond, Virginia, an American city with a gritty, industrial edge along the James River. The air buzzed with anticipation as Conrad Stoltz and Nico Lebrun stood on the edge of an arena that was completely new to them. Both 28 years old, both eager to prove themselves, yet hailing from wildly different backgrounds.

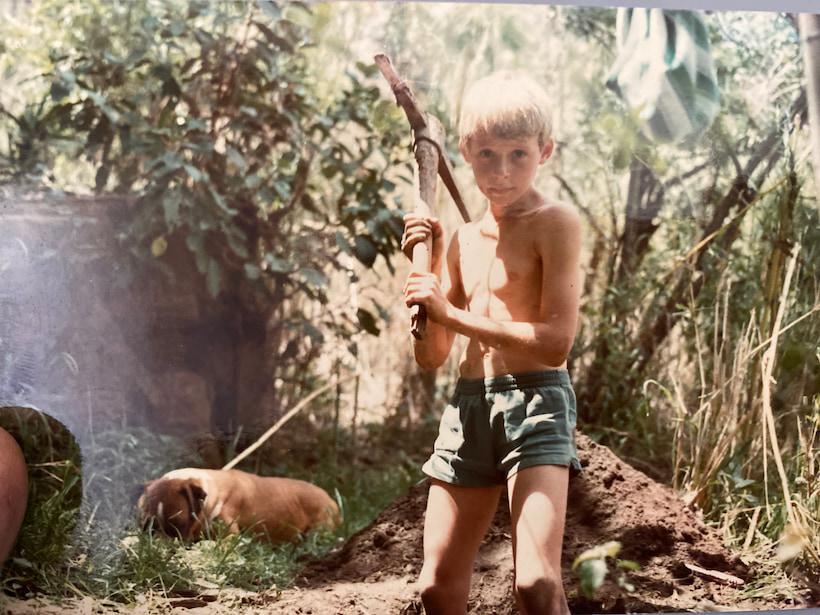

Conrad “The Caveman” Stoltz, had grown up bashing through the rugged terrains of South Africa, while Nico “The Professor” Lebrun, had spent his early years calculating his steps in the isolated mountains of the French Alps. Neither knew it then, but this initiation into XTERRA would be the start of something that would shape the rest of their careers and cement their legacies in the sport.

It wasn’t just another race. They both felt it, and that pulsating tension in the air hinted that this was no ordinary triathlon. It was their first-ever XTERRA race, a format that pushes boundaries and blends nature with competition. Both came to Richmond with something to prove. They had both already seen success in other sports—Stoltz, a two-time Olympian with a strong background in road triathlon, and Lebrun, a champion in duathlon—but XTERRA was different. It was raw. It was uncharted territory for both of them, and neither knew what awaited them on that course.

For Stoltz, the adventure began before he even hit the start line. He was used to technical challenges, but his preparation for this race was anything but smooth. “I borrowed a mountain bike from Joe Umphenour, who was with me at the US Olympic Training Center in Colorado Springs,” Stoltz recalled. The bike was a strange contraption, a Soft Ride mountain bike without suspension forks. “It had a flexi-stem, and I thought I could get away with it,” he laughed, remembering the bike’s wacky design. Armed with road pedals, road shoes, and a Speedo, he was far from ready for the technical nature of XTERRA. "The bike didn’t have room for a bottle cage, so I used a running Camelback around my waist for water."

When Stoltz arrived in Richmond, he was immediately blown away by the technicality of the course. "There were no designated mountain bike paths. It was fisherman's trails next to the banks of the James River, and I struggled so much on that bike." The course was a series of obstacles, raw and untamed, with sections requiring riders to jump from one island to another over massive rocks. He knew instantly that he wasn’t equipped for this. “I realized I needed mountain bike shoes and mountain bike pedals,” he admitted. After five days of pre-riding and primordial rigging his old cycling shoes back together with screws, The Caveman stood at the starting line, rattled but ready to dive into the unknown.

“It wasn’t just another race. They both felt it, and that pulsating tension in the air hinted that this was no ordinary triathlon.”

On the other side of the spectrum was Lebrun, who came to Richmond on a personal mission. "It was a big deal for me," he said. "My first time traveling to the US by myself." Unlike Stoltz, Lebrun wasn’t a newcomer to international racing, but this was different. He had been racing in long-distance duathlons, a bit of triathlon, and winter triathlons. But he was at a point where he needed to try something new. “I wasn’t able to be 100% financially stable from it,” he reflected. “You’re too old to keep playing around like this,” he had told himself before deciding to give XTERRA a shot. “I absolutely had to try it in the US,” he said.

Lebrun approached XTERRA Richmond not as a competitor ready to crush the field, but as an athlete seeking something different, a new experience. “When I went to Richmond, my mentality was to have fun,” he explained. “I discovered a great group around the race, the XTERRA Crew. They came to pick me up at the airport, helped with the hotel. Everything was new and crazy for me.” But even with that mindset, Lebrun was there to race, and it didn’t take long before his competitive spirit kicked in.

As the gun went off, the James River, with its tricky currents and sandbanks, greeted them. Stoltz launched into the water, embracing what he described as “the most technical swim I had ever done before.” The swim required navigating across multiple currents, swimming at an angle to avoid being pulled off course, and then running across an island before jumping back into the water for more. "I came out of the swim with the leaders, which was awesome," Stoltz said. But as soon as he got on the bike, the real challenge began. Mike Vine, a top Canadian XTERRA athlete, "came flying past me, and by the end of the bike, he had made four minutes on me," Stoltz remembered. "He completely blew me away."

Lebrun, on the other hand, was nowhere to be seen at the front during the swim. “I didn’t see him during the race because he’s typically a poor swimmer,” Stoltz said. While The Caveman was fighting off Mike Vine, Lebrun was quietly making his way through the field. "The course didn’t suit him so well because it was quite flat and technical, and Nico is more of a mountain guy," Stoltz explained. But The Professor's strength was analyzing and dissecting the bike and the run, and that’s where he excelled.

As Stoltz struggled on the technical course, dealing with a dropped chain and making adjustments, two more riders passed him—former XTERRA World Champions, Ned Overend and Steve Larsen from the USA. “I kept them in sight towards the end of the bike,” Stoltz said. But by the time they hit the run, he was holding on for second. He wasn’t the fastest runner, but in XTERRA, the ruggedness of the run levels the playing field. He managed to finish in second place, which for his first XTERRA was a great result. "I wasn’t a fantastic runner," he admitted, "but in XTERRA, I ran decent."

Lebrun crossed the finish line in third, thrilled with his performance. “I was really happy with that,” he said. “At the time, I didn’t know Conrad Stoltz at all.” It was only later that Lebrun realized who he had been racing against. "He was from South Africa, coming from road triathlon and the Olympics, while I was coming from duathlon. We were two rookies, both coming from different types of races.”

After the race, they finally crossed paths. Stoltz was struck by Lebrun’s minimal English, and offered to help with translation, tapping into his own experience from racing in France. "I spoke French, so I helped him with his translation with the organizers," Stoltz said. “I enjoyed it. Being a foreigner in the States, it was really cool to connect with other foreigners.”

"Neither knew it then, but this initiation into XTERRA would shape the rest of their careers and cement their legacies in the sport."

But even in their first meeting, their differences were clear. Stoltz had made a name for himself as a fearless competitor, charging through technical courses, unafraid to crash, while Lebrun was more calculated, studying every inch of the course. "Nico would scout the lines before the race,” Stoltz explained. “I would get there first, but by the end of a technical section, he would overtake me."

Their contrasting styles would define their careers in the years to come. But in Richmond 2001, they were two awestruck athletes from completely different worlds, standing on the edge of a new frontier in off-road triathlon. Neither could have known that they would go on to become two of the most celebrated XTERRA athletes in history.